Behind the Grids: How Kriging Helped Map Alberta’s Groundwater and Geology

Roger Clissold, Founder and Principal Hydrogeologist at Hydrogeological Consultants Ltd. (HCL), has a long history of turning complex, sparse water well data into usable, public resources. And for decades, his firm has relied on the gridding capabilities of Surfer to tackle massive, province-wide projects—most notably, mapping the groundwater resources for approximately 40% of Alberta, Canada, an area that’s around 277,000 square kilometers, or about the size of a state.

A Long History of Gridding Innovation

HCL’s relationship with Surfer began in the early 1980s. A key moment was when one of their employees returned from a groundwater modeling course in Denver, Colorado, bringing back essential knowledge of the program. The only issue? Surfer didn’t have Kriging. Roger and his team eagerly awaited the implementation of the gridding method, and, to the credit of Golden Software’s product team, Kriging was available within a couple of months, making Surfer the go-to software at HCL.

“At that particular time, we were paying around $300 for a Surfer license,” Roger recalled. “The only other program that was available for us to do gridding using the Kriging method was over $100,000. It was hugely expensive. But with Surfer, we had a $300 program, and we just came to love the software. We’ve worked with Surfer forever.”

The Massive Project: Mapping Alberta’s Groundwater

It was the unique, cost-effective power of Surfer’s gridding capabilities that equipped HCL to take on its most significant and defining project: mapping the groundwater resources across the entire “white area” of Alberta, which refers to the settled, populated portion of the province as opposed to the forested “green area” of the province.

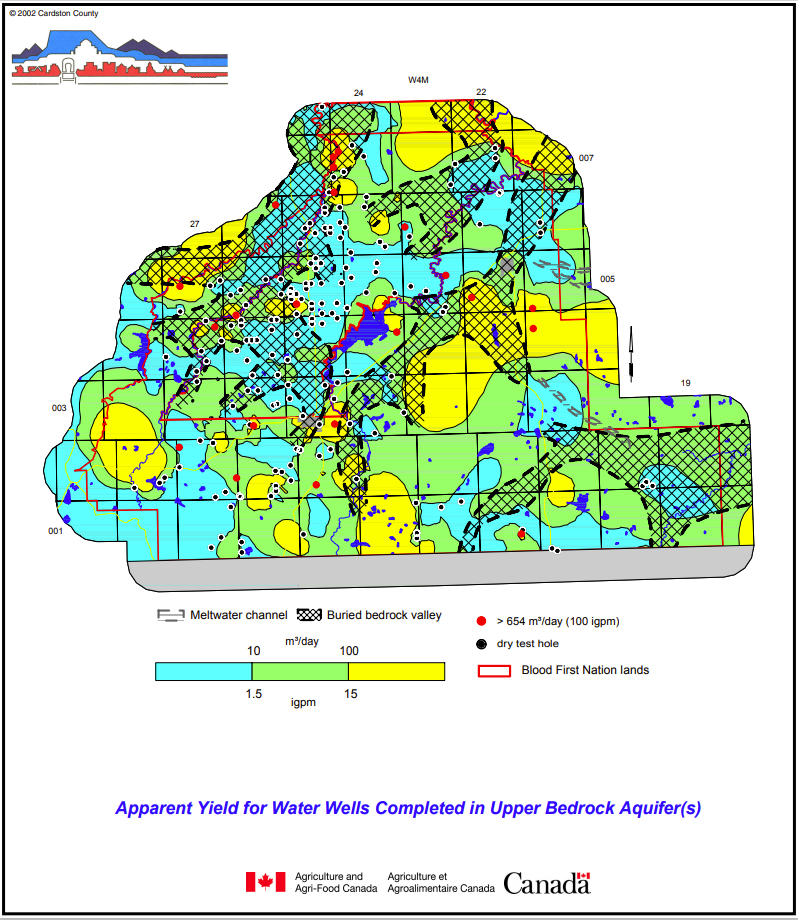

The project began with the federal government’s involvement through the Prairie Farm and Rehabilitation Administration (PFRA). PFRA provided some of the funds for local counties to hire HCL to map the province’s groundwater resources. The goal was to transform data—which had primarily been a paper system—into a searchable, accessible digital system (e.g. GIS) and deliver a product to the public that would answer essential questions about their land, including expected groundwater supply and related elements like:

- Drilling depth required

- Volume of groundwater available

- Quality of the groundwater

To accomplish this, Roger and his team built an incredibly massive database. While the provincial government required water well drillers to provide basic data, HCL created its own database, which was, and still is, constantly updated with new information, including extensive groundwater chemistry and field-verification data.

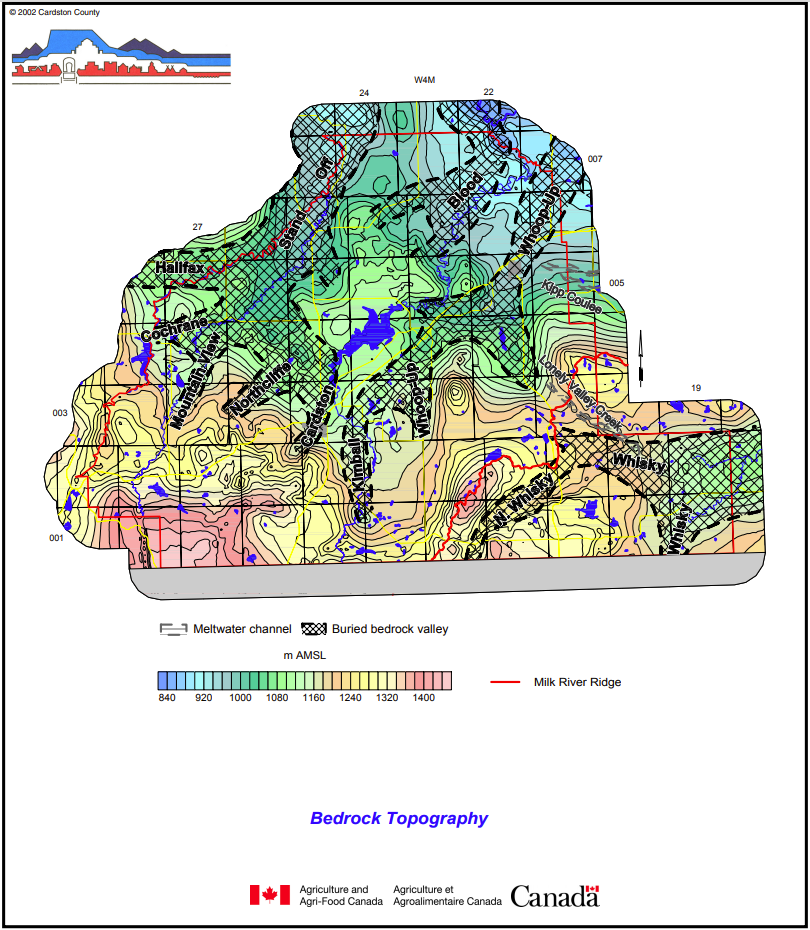

Additionally, the government funds paved the way for the precise positioning of thousands of water wells, improving the spatial control from a general quarter-section (800 meters by 800 meters area) to a specific set of coordinates. With this better spatial control, HCL could obtain accurate elevation data, which made their final results far more meaningful for the end-user.

Surfer Grids: The Core of the Solution

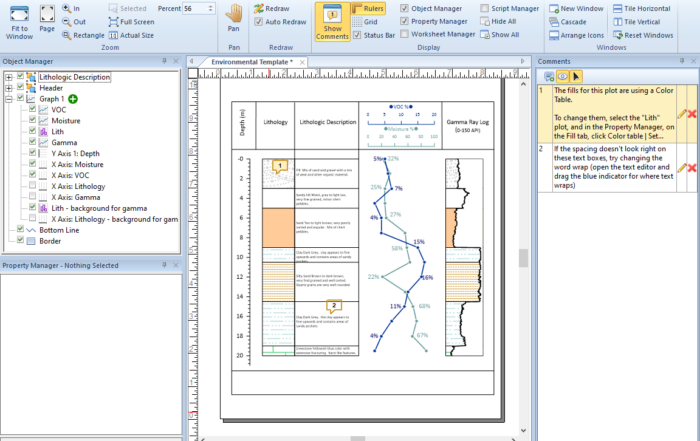

While gathering data for many of Alberta’s counties, HCL gridded the information using Surfer and built a query system to make their database easier to navigate. That way, an end-user could simply type in their coordinates and receive an instant report detailing the expected aquifer interval, groundwater volume, groundwater quality, and initially even the estimated cost to drill a water well.

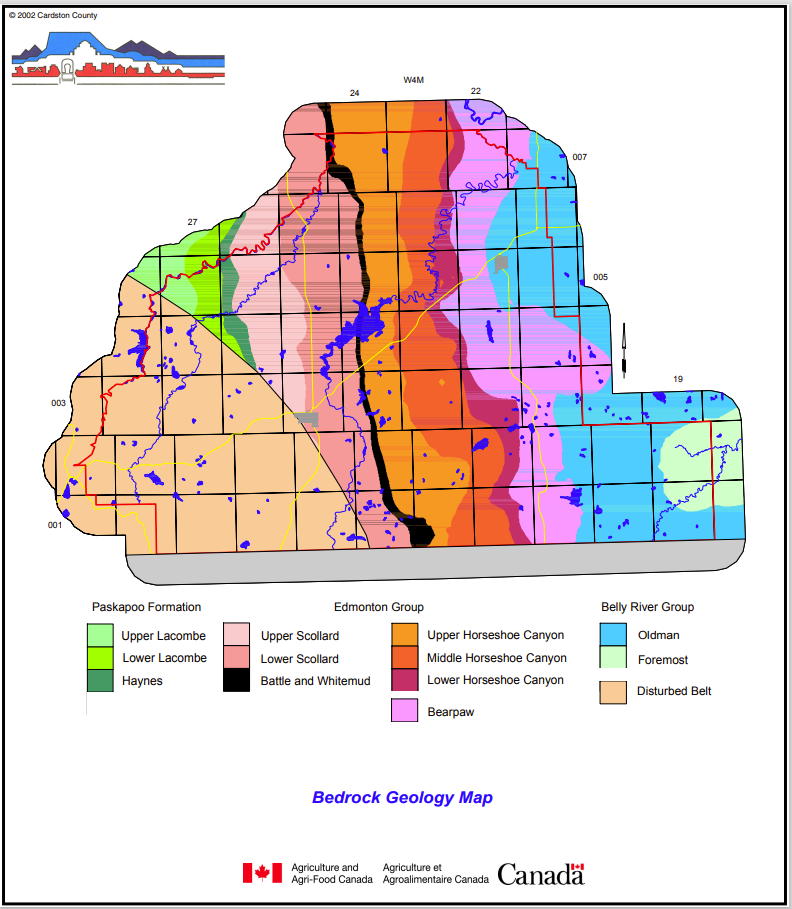

On top of that, HCL was also asked to standardize Alberta’s diverse geological nomenclature. Historically, different areas of the province had used different names for the same formations, leading to confusion. For example, the “Viking Formation” in the northern part of the province and the “Bow Island Formation” in the southern part of the province were one and the same.

“The federal government asked us, ‘Can’t you make this more uniform across the whole province?’” Roger said. “So, we ended up mapping the geology of all of Alberta, and we gridded everything with Surfer.”

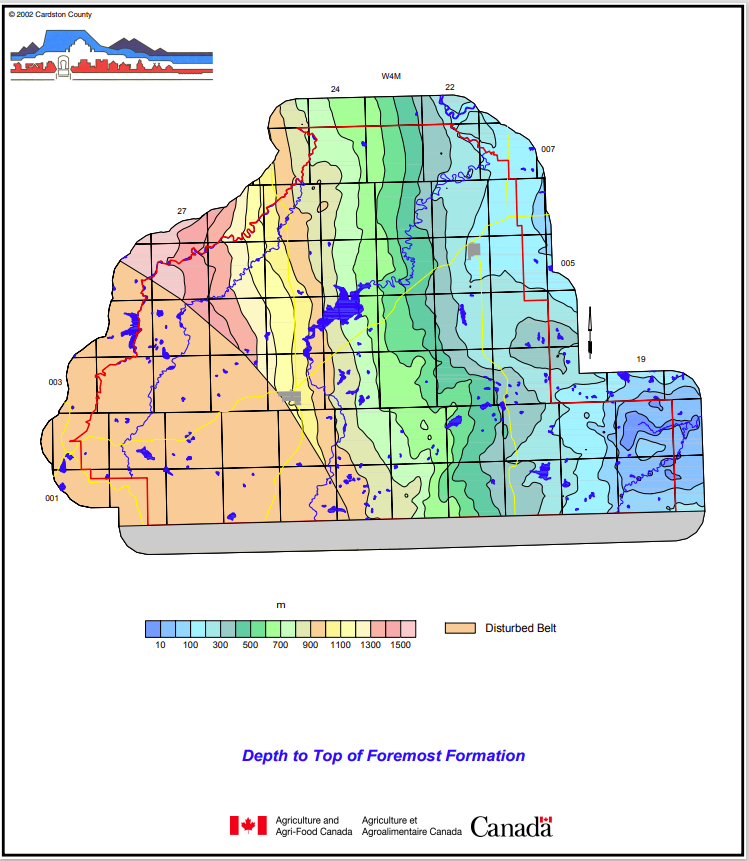

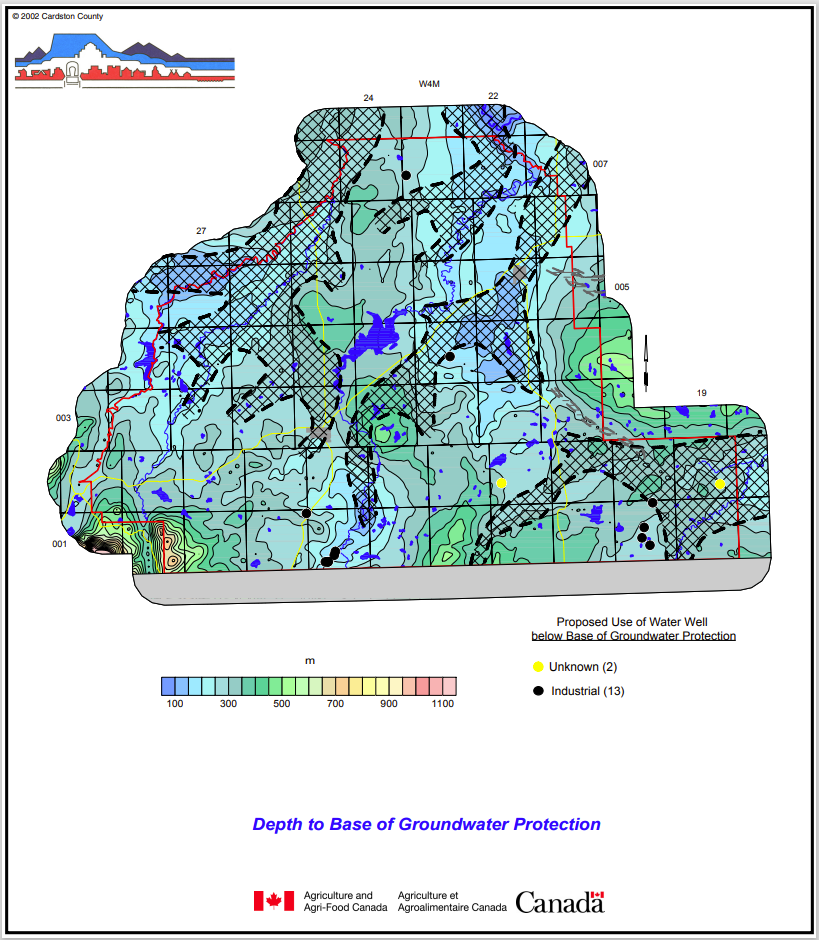

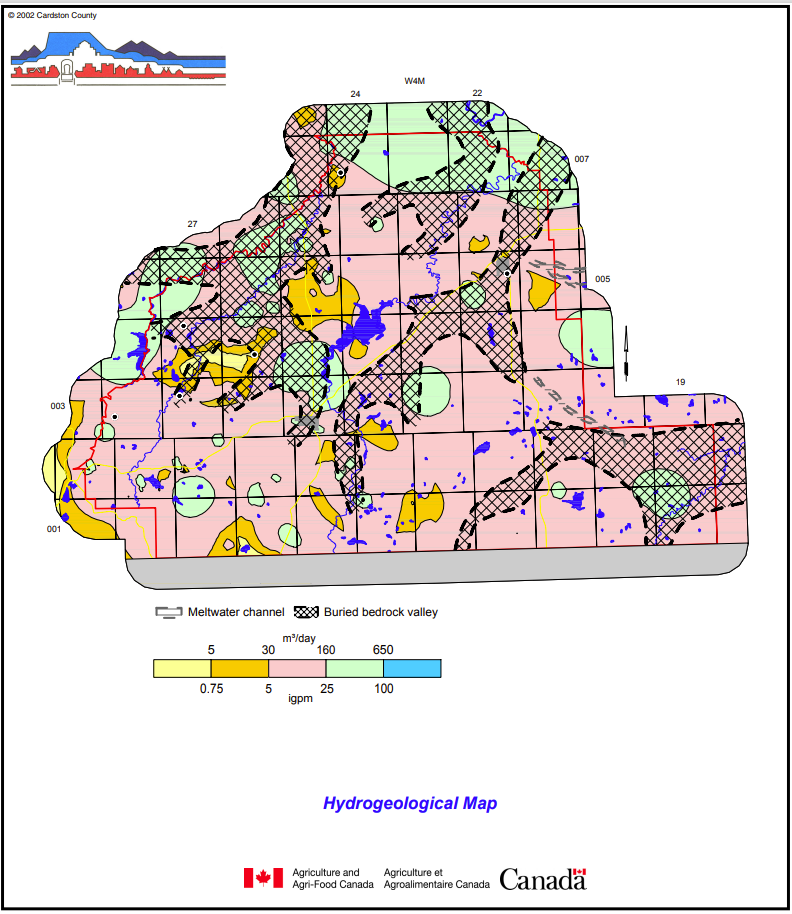

On HCL’s website, you can see all the reports they did for their province-wide project with the federal government. One example that Roger highlighted is the Cardston County Report, which includes texts and many visuals.

“The index map is the topography,” Roger said when briefly walking through the report. “We have one grid for the entire province of Alberta, but these individual areas in the province that we gridded [like Cardston County] are how it all started. The second map in the report shows the locations of water wells and springs. All of those were gridded with Surfer. We didn’t use anything else. But the whole functionality that made the visuals really useful was the fact that we could build a query to query these grids.”

The Kriging Method: Art and Science

The remarkable ability to build a query system that pulls critical hydrogeological information was entirely dependent on having good grids, which for HCL were always created using the Kriging method in Surfer.

For Roger and his team, Kriging was widely regarded as the best way to grid highly variable hydrogeological data because it provided the closest result possible to reality. Roger noted that at an International Association of Hydrogeologists (IAH) conference in 1995, Surfer was essentially the only program being used by hydrogeologists from many countries around the world, a testament to its “phenomenal penetration of the hydrogeological market” due to its effective features, including its gridding capabilities. However, Roger still offers a vital warning that scientists should keep in mind: “Kriging is great, but it isn’t reality.”

Roger explained that Alberta’s hydrogeology is highly variable, largely due to fracturing caused by the ground rebounding because of continental ice sheets melting and the westward movement of the Rocky Mountains caused by continental drift. You can move just one meter and find a totally different water well yield. While Kriging did an excellent job of interpolating the data between known water well points, it still gave an estimation. That didn’t mean it was untrustworthy. It just meant the gridding method didn’t show reality, and Roger kept that in mind, even though he thought Kriging did a great job overall.

“Part of the work we do is trying to identify these fractures from surficial features, and that’s got a lot of art in it,” Roger said. “We still don’t have much science behind it. It’s more art than science. But generally, if you have 10 water wells in an immediate area, they probably reflect better what’s going on. The highest yield will be on those fractures. But off those fractures, where most water wells are completed, the data that we have from the surrounding water wells are usually the best indicators. So, what you have is this value here and here, then Kriging takes over, and it does a great job. It really is an excellent method of gridding.”

The Data That Powers Global Decisions

The work Roger and his team accomplished shows how powerful tools can solve large-scale problems. By leveraging Surfer’s Kriging capabilities, HCL transformed scattered, raw data into a uniform, queryable resource for an entire province. As a result, they not only delivered a better understanding of Alberta’s hydrogeology but also provided a publicly available tool that empowers the community to make informed decisions about one of their most vital resources: groundwater.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe to our blog so you never miss an update!