A Glimpse Into the University of South Florida’s Field Camp: How the Geophysics Course Is Guiding & Equipping Students

When you’re pursuing a geology degree at the University of South Florida (USF), there’s one experience that truly transforms your education from theory to practicality: field camp. In the geophysics session that USF Instructor Judy McIlrath teaches along with other colleagues, students get an unforgettable lesson packed with hands-on learning, innovative software tools, and meaningful data interpretation. By the time they’re finished, they’re not just equipped to effectively survey a field with instruments; they’re also ready to uncover the stories hidden beneath the Earth’s surface to ensure they’re prepared for successful geoscience careers.

A Modern Take on a Traditional Requirement

Field camp has long been a cornerstone of geology education. However, when Judy was an undergraduate student at USF, attending field camp meant flying out of the state for six weeks.

“When I was a student, there wasn’t a field camp,” Judy explained. “You were still required to do a field camp, but you had to go to a different university and pay out-of-state tuition, and it was really expensive.”

This format came with challenges, especially for students juggling jobs, family obligations, and other responsibilities. Fortunately, a new department chair who came on board in 2001 quickly recognized this and advocated to transform the traditional model into something more accessible and practical: an in-house field camp with five separate two-week field courses. Each would offer immersive experiences, and among them was the geophysics course that Judy and her colleagues proudly teach today. The only hangup? Florida wasn’t the ideal place to host the entire field camp.

“Could we do this field camp in Florida? Yes,” Judy said. “Is there any volcanism in Florida? No. If we wanted to do magnetic surveys in the state, we’d probably have to do them over a landfill or a junkyard.”

To circumvent this reality and give students real-world experiences, the department came to a solution. Some courses would be in Florida, like the hydrogeology and coastal geology sessions. Others—like the geophysics course—would take place in Idaho, where students have access to a wide variety of volcanic and tectonic features that simply don’t exist in Florida. After coming to this decision and implementing it, the benefits have been clear.

The Idaho location is a geologist’s dream: a valley between two mountain ranges, home to ancient volcanic activity, faults, and even a nearby copper mine. On top of studying in this ideal location, students also have access to a 40-by-80-foot field station that USF built in 2024 to provide a base that supports serious research.

“We used to be nomads, sometimes camping, sometimes staying in places for free,” Judy shares. “Today, we have this fantastic building. It’s a little more than a shell for now, but if we keep working at it, we can have a world-class research facility that other people can use.”

Until that day comes, the main people using the facility are USF geology students; they’re helping lay the foundation for what could be a significant research program in the future—and they’re doing it while gaining practical knowledge they couldn’t get in Florida. Like Judy articulated so clearly: “For our students, they cannot get experience and be well-rounded geologists if they do everything in Florida. They just can’t.”

What Students Do in the Geophysics Course

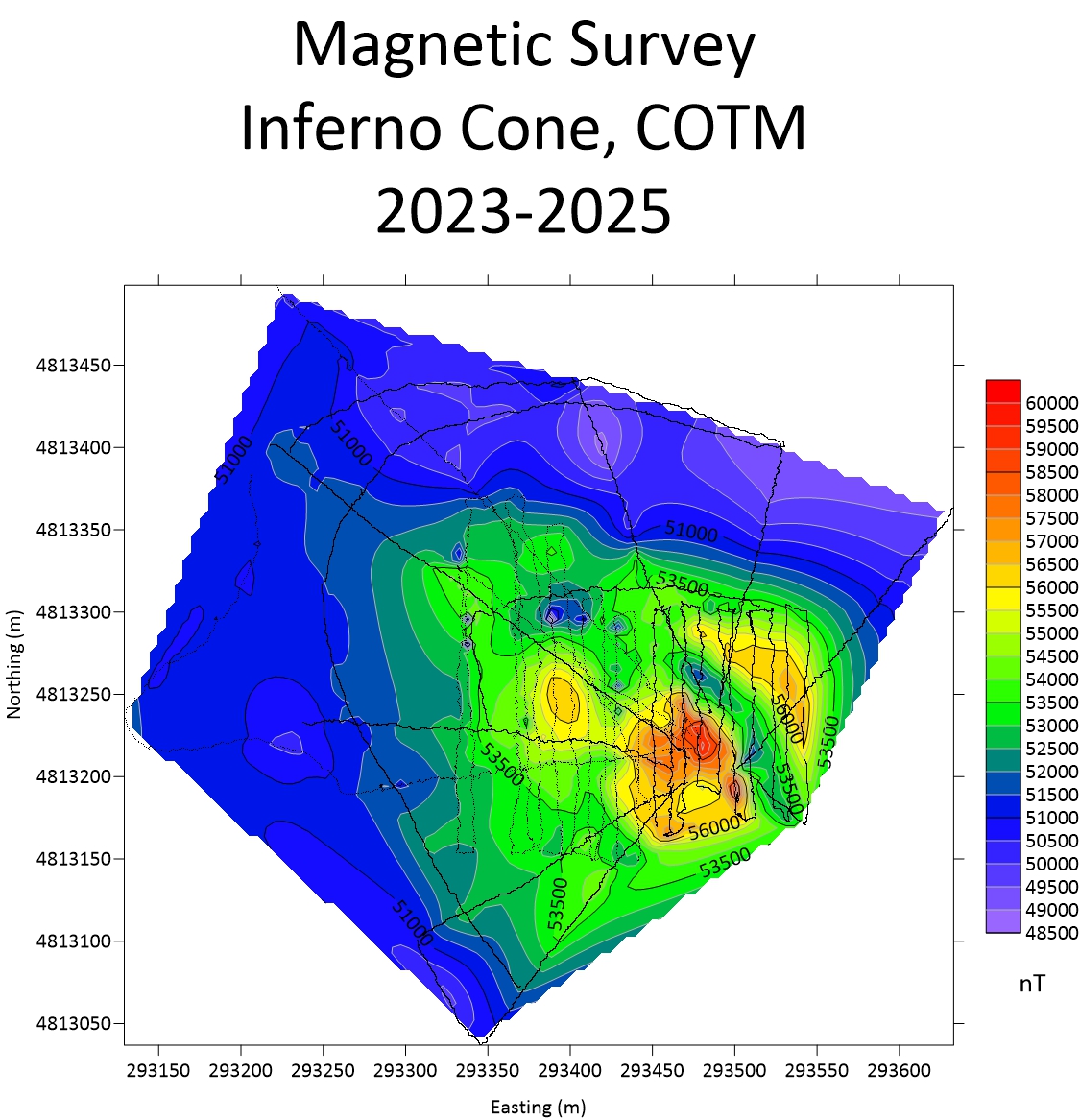

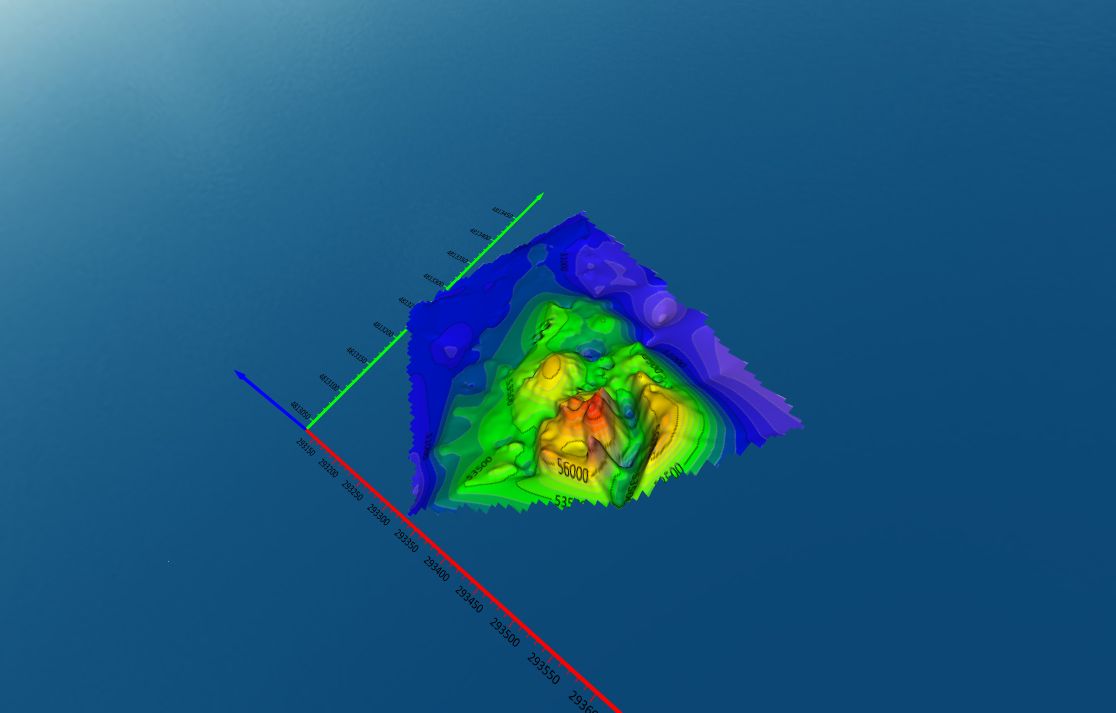

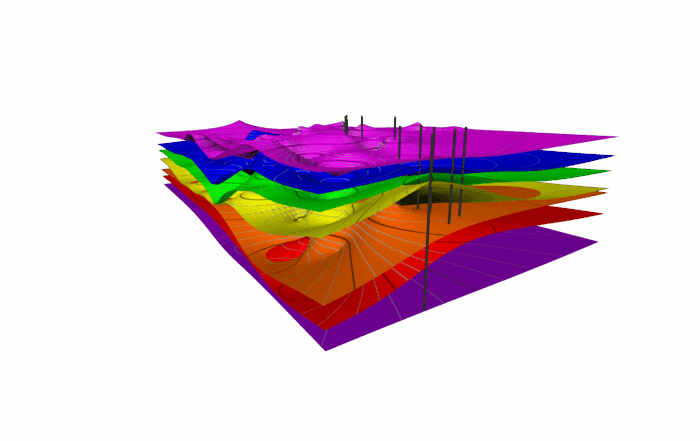

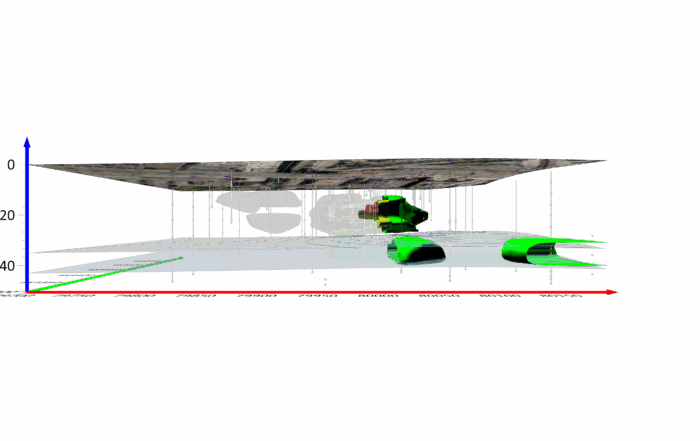

When it comes to creating well-rounded geologists, Judy and her colleagues ensure the two-week geophysics course gives students hands-on experience with real equipment such as ground-penetrating radar, magnetometers, seismic reflection systems, and resistivity survey tools—all of which they can use to gather data. To jumpstart this data collection process, they choose new targets for surveys every year. But if the data from a previous year looks interesting, the class will revisit the site the following year to build on prior findings. Overall, the goal is for students to spend four full days collecting data using different methods before processing and interpreting it.

“Our goal during the field camp is to use different data collection methods in a particular location so that we can get a better picture of the geology,” Judy said. “It’s important that students understand that magnetics is going to show you something, but it won’t give you a complete picture. If you pair magnetics with ground-penetrating radar, neither one of them will give you a complete picture, but together you can tease out what might lie beneath the surface.”

The region students are learning in offers plenty of geological features to investigate: igneous dikes, sills, rifts, and faults—all formed by volcanic activity. Students might study areas impacted by earthquakes, like the 1983 event along the base of Bora Peak, Idaho’s highest summit. They might also hike across volcanoes at Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve, an experience made possible by a special research permit that USF acquired. However, while all the opportunities for exploration and research are abundant, it’s still normal for students to initially feel overwhelmed during class.

“It’s so different from what they’ve done in other courses, but in a good way,” Judy explained.

Students still take field notes, draw sketches, and document equipment and procedures like they do in other field camp sessions. But in the geophysics course, they also push buttons, swing sledgehammers, and carry heavy gear all day. What they don’t know when they first start the course, however, is that carrying and using all the equipment is the easiest part.

“You can teach a monkey how to push a button, but you’re not going to make a lot of money just knowing how to push the button,” Judy explained. “Learning how to push the button is the easy part. For the magnetics survey, we walk all day with an instrument attached to our backs, and it’s heavy, so it’s physically demanding. Even that, though, is something just about anybody in geology can do. It’s when we get back—when I hand them a thumb drive with a CSV file—and we open it in Surfer, try to make a map, and figure out what that map means that things get hard.”

Why Surfer Is a Game-Changer

Before USF started using Golden Software’s Surfer, Judy dreaded teaching the field camp’s geophysics course because plotting the data was such a headache.

“I’m not a coder,” Judy admitted. “I would lose a semicolon, so the code wouldn’t work. I became very frustrated every single time I tried to plot the data. I dreaded teaching the field camp, knowing I had to run these codes and make adjustments and couldn’t make any mistakes. Surfer is very forgiving, and I love it.”

Surfer makes it easy for Judy and the students to visualize their data—but not just from a coding perspective. The software also keeps them from having to do things by hand. To help students see the ease that Surfer provides, Judy requires them to start with a paper exercise, contouring about 50 data points by hand. That way, they can appreciate just how much Surfer streamlines the visualization process when it comes to mapping 100,000 points in a day.

“It’s super good for them to see the difference between plotting it by hand and struggling versus letting the computer do the work for them but not understanding what they are looking at,” Judy explained.

Emphasizing the Need to Tell the Data’s Story

After the initial hand-drawing lesson, Judy sits with her students and dives into Surfer so they have a basic understanding of how to create a data visualization. Specifically, she shows them how to design a magnetic map using UTM coordinates, and then she has them repeat the process on their own using latitude and longitude to overlay the data in Google Earth. Afterward, Judy helps the students interpret their maps so they can effectively communicate findings.

By the end of the process, students know how to:

- Import and map magnetic survey data

- Annotate maps with transects, power lines, and field notes

- Add layers showing key features like fences, metal debris, and volcanic structures

- Interpret what the colors and anomalies in their maps actually mean

It’s an experience that ensures students don’t just create visuals but also use them to make sense of their data and tell a story—a key differentiator between pushing buttons and becoming a geophysicist. To bring this point home, Judy often tells her class a story about two USF alumni: herself, who became an instructor, and a friend who became a geophysicist. Both earned master’s degrees and have successful careers, even though their jobs look different.

“He lives in a house in Steamboat Springs, Colorado—five bedrooms, four baths, on 36 acres of land,” Judy explained. “I live in a 1,000-square-foot home in Brandon, Florida. He made lots of money being a geophysicist, and I could have gone that direction, but I love what I do, and he likes what he does, so I tell students that you can learn how to push all the buttons, and you can walk around with instruments for the rest of your life, and you’ll get paid okay to do that. But if you can process the data and tell a story about what that map means, that’s where you make the money.”

Student Reactions and Real-World Outcomes

Despite the challenges students may experience during field camp, many of them walk away from the geophysics course with a sense of clarity and a sense of purpose. In fact, one student recently emailed Judy to express how much he enjoyed the geophysics course and that he planned to pursue a career in the field.

“He reminded me that his sister took my class, and something I said made him decide to go the geology pathway as well,” Judy shared. “He said he learned the most from the geophysics course.”

That kind of impact isn’t unusual. Judy frequently hears positive feedback from students who enjoyed the challenging but rewarding work the geophysics course offers. The session doesn’t just prepare them to walk across fields and collect data. It also teaches them to make sense of the world beneath their feet and help others do the same. But the most rewarding part for Judy isn’t the feedback, although it’s wonderful to receive. Instead, it’s seeing students she met in her Introduction to Geology course—which she teaches during the academic year—leave equipped and primed for success when they were initially unsure what they wanted to do.

“For me, seeing a student from the Introduction to Geology course transition from not really knowing if they’re making the right choice to saying ‘I’m so glad I did this and this is a good pathway for me,’ and then watching them leave school, knowing they’re going to be successful in wherever or whatever direction they go is really rewarding for me.”

Want more real-world stories highlighting what’s happening in the world of geoscience? Subscribe to our blog so you never miss a story!