The Change Beneath the Surface: Tracking the Decrease of Freshwater Clam Species Diversity in Iowa

Archaeologist and Iowa State University Professor Matthew Hill recently completed a research project investigating the health of freshwater clams in the Des Moines River, a 525-mile waterway that eventually joins the Mississippi River near Keokuk, Iowa. Matthew’s research project set out to answer a single question: when did the Des Moines River’s clam species die off?

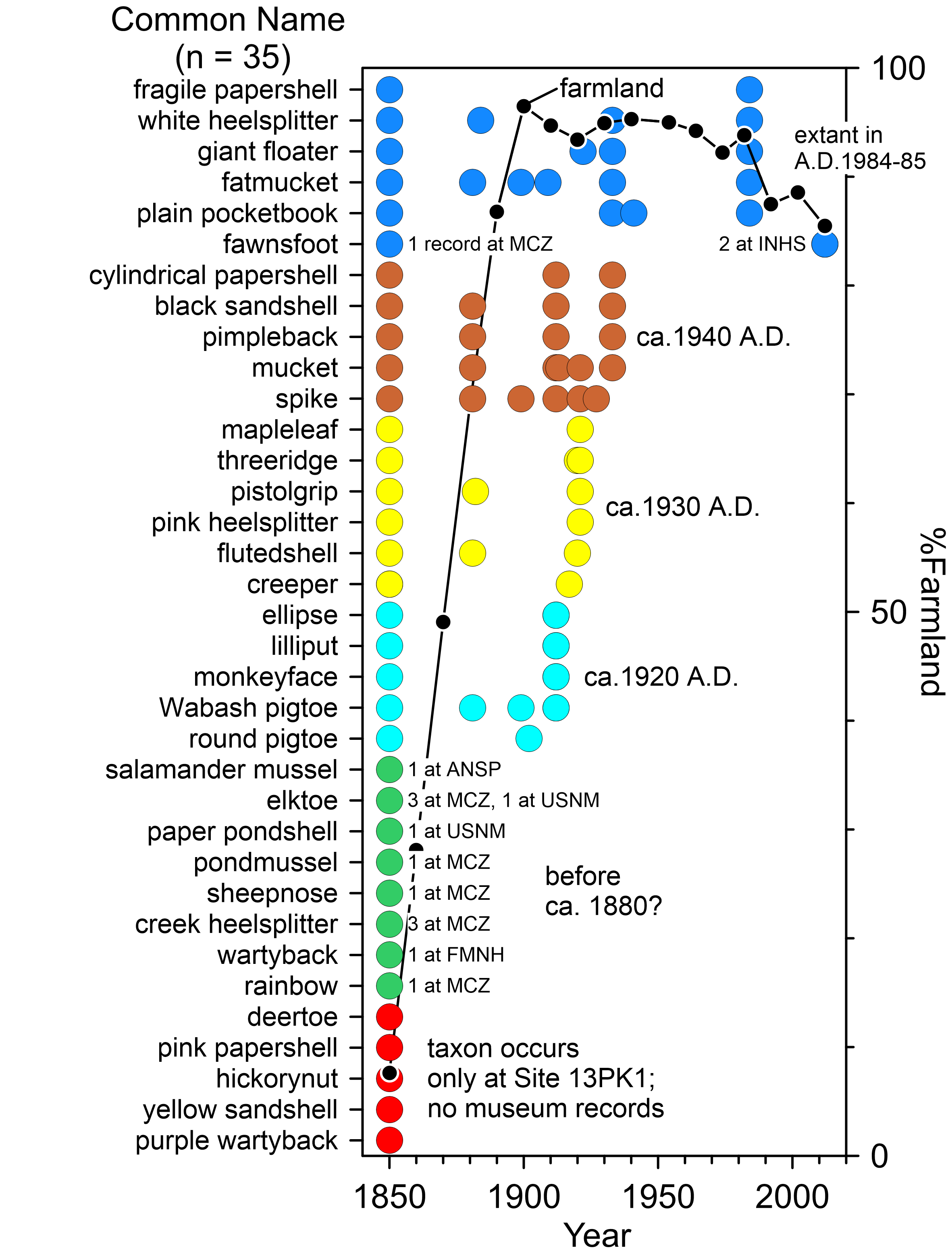

After gathering archaeological evidence, the date of collection on museum specimens, and historical farming data, and visualizing his findings in Grapher, Matthew uncovered a major ecological shift. The number of clam species in the Des Moines River had declined significantly throughout the years, from 35 species several centuries before the arrival of Europeans to just six species today. When he compared this decline to land use data across Iowa, one potential culprit stood out: the conversion of Iowa’s native prairies to farmland.

A Surge in Cultivation—and a Possible Clue

To understand what may have caused the sharp decline in freshwater clams, Matthew turned to Iowa’s historical agricultural records. Using data from the U.S. Agricultural Census, he overlaid cultivation trends with clam extirpation timelines in a Grapher visualization. What emerged was a compelling correlation.

“If you look at the chart, you’ll see the second Y-axis labeled as ‘percent farmland,’” Matthew explained. “The Agricultural Census began collecting this data in about 1850. If you go online, they provide information on the percentage of land under cultivation in a particular state.”

Based on the data, Matthew found that in 1850, only around 7% of Iowa’s land was being farmed. But by 1900—just 50 years later—over 90% of the state had been converted to cropland.

“That means all of Iowa was basically cultivated,” Matthew said. “That’s brutal. That happened within 50 years.”

What drove this rapid transformation? Matthew explained it simply: “Iowa was perfect for it. You had steel plows from John Deere, and all of Iowa is at a latitude where, precipitation-wise, the entire state can be cultivated. You can’t do that in Wisconsin or Minnesota because it gets too cold. The number of frost-free days is so high that corn can’t finish growing. Iowa is perfect.”

How Cultivation Contributed to the Decline of Freshwater Clams

The rapid rise in cultivation likely altered the Des Moines River’s ecosystem. The surge in farmland increased sediment runoff, changed water chemistry, and disturbed freshwater clams’ habitats—ultimately leading to the disappearance of many species.

“This is before we had buffers along rivers, and before conservation practices really took hold,” Matthew explained. “Everything was going into the rivers—chemicals, nitrates, phosphates, manure—and especially sediment. That sediment erodes from farm fields and smothers mussels.”

This influx of pollutants likely had devastating effects on freshwater clams, which are highly sensitive to water quality and sedimentation. The chart Matthew created in Grapher illustrates the timeline of mussel species extirpation in relation to the percentage of Iowa farmland. Each dot on the chart represents the last known observation of a particular species in the Des Moines River. In 1850, 35 different species of freshwater clams were documented in the waterway. By 1950, only six remained.

“When you tie the percent of farmland to when these animals went extinct, we see that right after 1900, when Iowa was 90% cultivated, they all began to go extinct,” Matthew explained. “And we know when the last time a particular animal was captured, because there are dates with this information. The last time the Wabash Pigtoe and Threeridge were collected was about 1920. The last time a spike was captured was about 1930.”

Ultimately, Matthew’s visualization makes a strong link between increased cultivation and a decrease in freshwater clams. As seen on the chart, when cultivation rose, biodiversity fell.

“If you were to go out to the Des Moines River in Central Iowa, this is what you will find: five species,” Matthew said, plainly. “But 120 years ago, you would’ve found 35 species of freshwater clams.”

A Closer Look at the Past

Matthew’s research on the freshwater clams in the Des Moines River offers a potential cautionary tale about how land use can shape, and in some cases, significantly alter ecosystems. But that being said, his research also opens the door to opportunity. With his visualization, Matt can help stakeholders make more informed decisions today that could preserve, and even restore, freshwater ecosystems for the future.

Want to keep up with the latest happenings and projects in the world of geoscience? Subscribe to our blog so you never miss a story!